Daylighting for Visual Comfort and Energy Conservation in Offices

Kaftan’s Ph.D. Dissertation (First Part)

Author: Dr. Eran Kaftan, Advisor: Prof. Evyatar Erell

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Department of Man in the Desert, October 2012

Abstract

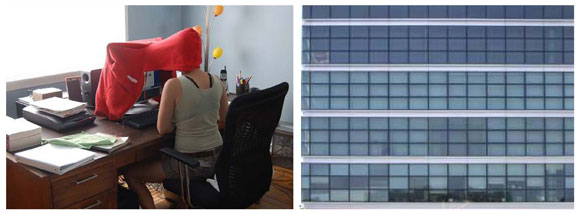

Design Problem: extensive glass facades, a popular architectural feature, create a very problematic visual conditions due to glare (left) or façade covered by curtains, with no use of daylight but merely artificial lights (right).

The use of large glass facades, currently a popular architectural feature, does not ensure better use of daylight, as is often suggested, and in fact may create glare hazards. As a result, we often see windows that are permanently covered by closed blinds or opaque curtains, with electric lights switched on even during the daytime.

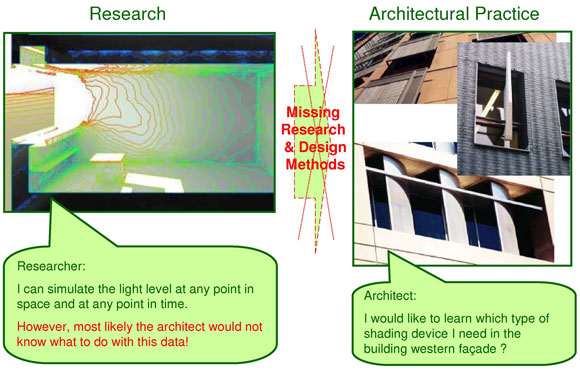

Methodological Problem: research in architectural practice encounters difficulties since most daylighting research methodologies and tools designed for academia. However, the academic research process is fundamentally different from processes in architectural practice.

The research consists of two parts: first, a study of daylighting in offices in sunny locations, which was used to draw mainly prescriptive and performance recommendations, as well as to serve as a case study for a research process. From the architect’s point of view, both performance and prescriptive recommendations are somewhat limited, since they do not teach how to design optimized or unique solutions. Therefore, in addition, the second part of this research consists of the development of methodological recommendations for the integration of daylighting research during the architectural design process.

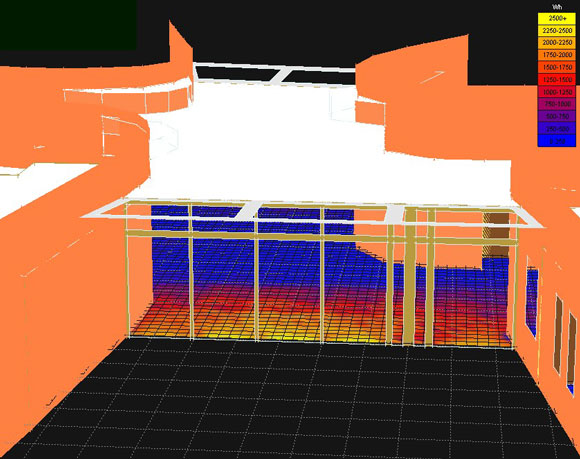

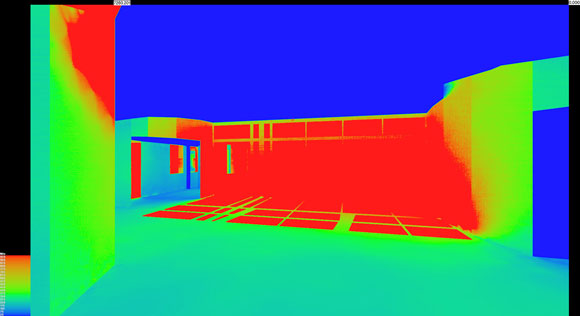

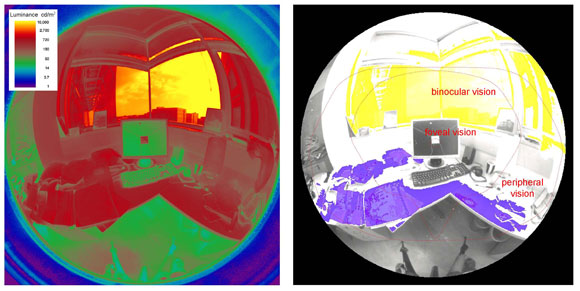

Glare Analysis Methodology: measurements and analysis of glare were carried out by using High Dynamic Range Photography (Left) to generate Luminance Map (Right).

The first part of the research included a field survey of offices and a controlled experiment on daylighting. The field survey was carried out to identify some of the causes for extensive use of artificial lights in Israeli offices, where substantial energy saving may be achieved through the use of daylight; and to examine various survey techniques.

Field Survey of Offices: luminance map (left) and glare analysis (right) of case study # 015.

The office suffers from problematic visual conditions: when blinds open, glare negatively affect the working environment quality; and when they are closed, the natural illuminance is low, requiring artificial lights. As a side effect, desirable view outside will often be blocked by shading systems due to glare.

The survey confirmed that offices often suffer from problematic visual conditions: When blinds or curtains are open, glare may affect the quality of the working environment negatively; and when they are closed, the result is often low natural illuminance, forcing the occupants to use artificial lights.

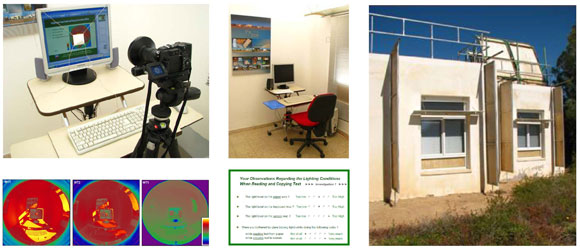

A Controlled Experiment on Daylighting: a statistical survey of visual comfort in a controlled office environment; including objective measurements (left) and subjective responses to a questionnaire (middle), carried out simultaneously in two identical rooms (right).

The controlled experiment was carried out to evaluate the effectiveness of several daylighting systems and office layouts with regard to visual comfort and energy conservation in sunny regions, and to evaluate the predictive power of several glare indices. The survey, which included 59 subjects, was carried out in a daylit environment set up to simulate a typical office. Visual comfort was evaluated based on both objective measurements and subjective responses to a questionnaire.

Selected Results — A light shelf: A light shelf located between upper daylight windows and lower view windows, with blinds closed when low solar, was found as good means for providing sufficient natural illuminance without glare.

Overall, the experiment showed that the effect of tinted glazing and desk position on visual comfort was quite modest. The effect of blinds on visual comfort was positive (although blinds require frequent adjustment, which is rarely done in practice). A light shelf with blinds deployed below it may provide high quality daylight: it reduces glare in a working area near the window while enabling higher illuminance levels deeper in the office. Subjects were happy with relatively high levels of horizontal illuminance at their desk, well above the minimum recommended in ISO Standard 8995 for the illumination of work spaces.

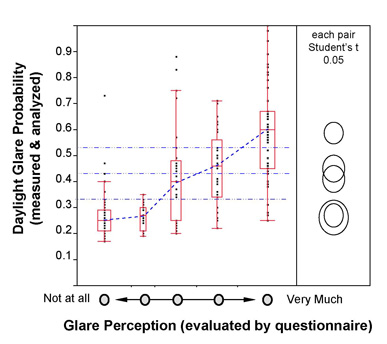

Selected Results — Validation of Glare Indices for Sunny Regions: A clear relationship identified between measurements and the subjects’ assessment of glare, enables safer use of these indices for daylighting design and research in sunny regions.

While the glare indices DGI, UGR, CGI, and VCP may differentiate between glare and non-glare conditions, they are less effective in distinguishing between various levels of glare in brightly lit offices. In contrast, the Daylight Glare Probability (DGP) index, which was designed specifically for daylit environments (but which is based on a survey conducted in Germany and Denmark, countries with relatively overcast skies, and while using Venetian blinds most of the time) was shown to be effective in Israel, too.

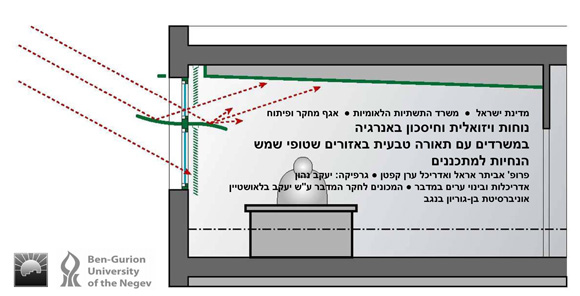

A Fundamental Daylight Solutions: a part of recommendations (in Hebrew) for better design of daylighting in sunny regions, available at http://www.bgu.ac.il/CDAUP/daylighting-guidelines-hebrew.pdf (Prof. Evyatar Erell & Dr. Eran Kaftan. 2011. The Israeli Ministry of National Infrastructures. 50p.).

Finally, conclusions from both investigations were used to generate local recommendations: guidelines for architects, submitted to the Israeli Ministry of National Infrastructures; and a proposal for a revision of the daylight section of the Israel Green Building Standard (Standard 5281).

Relevant Publications

Kaftan, Eran. 2012. Daylighting for Visual Comfort and Energy Conservation in Offices and the Development of Methodologies for Research in Architectural Practice. A Ph.D. Dissertation. Ben-GurionUniversity of the Negev, Israel.

Erell Evyatar, & Kaftan, Eran. 2011. Daylighting for Visual Comfort and Energy Conservation in Offices in Sunny Locations. A Research Report. Ministry of National Infrastructures, Israel.

Erell Evyatar, & Kaftan, Eran. 2011. Daylighting for Visual Comfort and Energy Conservation in Offices in Sunny Locations: Guidelines for Designers. Ministry of National Infrastructures, Israel.

Project of the Year 2012, in Research Category: the Emilio Ambasz Award for Green Architecture. “Positioning Workstations in Sunny Areas”. Published in Architecture of Israel (Architectural Quarterly). No. 91, pp 65 & 68. 2012.

Erell, Evyatar & Kaftan, Eran & Garb, Yaakov. (2014). Daylighting for Visual Comfort and Energy Conservation in Offices in Sunny Regions. Conference: 30th PLEA International Conference – Sustainable Habitat for Developing SocietiesAt: Ahmedabad, India.

Kaftan, Eran, 2015. The Science & Art of Daylighting Design. Electricity & People: periodical of the Society of Electrical and Electronics Engineers in Israel. No. 56. P 50.

Wienold, J., Iwata, T., Sarey Khanie, M., Erell, E., Kaftan, E., Rodriguez, R., … Andersen, M. (2019). Cross-validation and robustness of daylight glare metrics. Lighting Research & Technology, 51(7), 983–1013. The paper received the Leon Gaster Award from the Society of Light and Lighting (CISBE).

Geraldine Quek, Jan Wienold, Mandana Sarey Khanie, Evyatar Erell, Eran Kaftan, Athanasios Tzempelikos, Iason Konstantzos, Jens Christoffersen, Tilmann Kuhn, Marilyne Andersen. 2021. Comparing performance of discomfort glare metrics in high and low adaptation levels. Building and Environment, Volume 206, 2021.

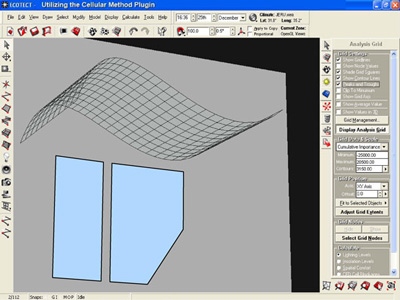

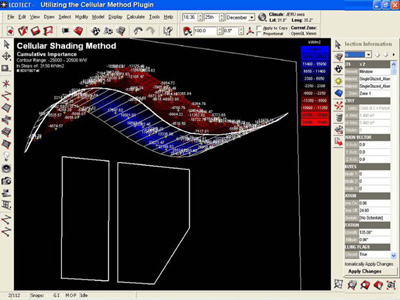

Autodesk Ecotect (2008)

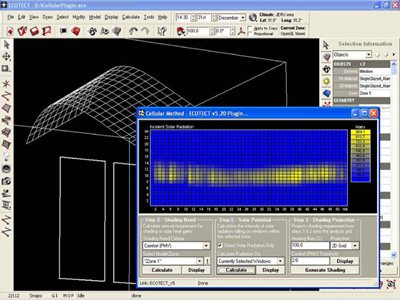

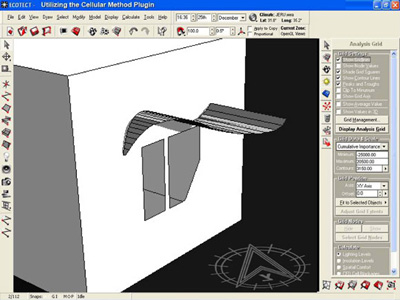

Autodesk Ecotect (2008) SHADERADE (Harvard University; 2011)

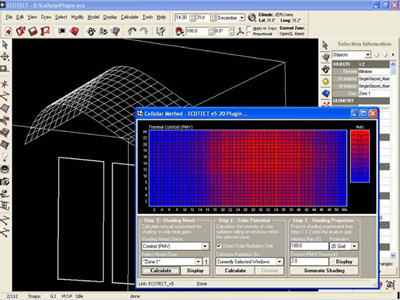

SHADERADE (Harvard University; 2011)